By now, everyone who has ever nibbled on chicken wings prepared in a particular style knows their origin story: in 1964, at the Anchor Bar, Teressa Bellissimo cut some wings in half, deep fried them, tossed them in hot sauce, and served them at the bar with celery sticks and blue cheese dressing. A star was born. Today, Buffalo is not just a city, it is a flavor applied to just about anything: snack foods, cauliflower, shrimp, pasta salad, mac & cheese, hamburgers, stuffed mushrooms, and even pizza.

The Buffalo affection for chicken wings is not limited to the Bellissimo version, however. The first appearance of chicken wings in the Buffalo telephone book was courtesy of John M. Young (1935-1988). Young, an African-American entrepreneur, opened a restaurant in 1966 called “Wings & Things” at 1313 Jefferson Avenue. His wings were uncut, breaded, deep-fried, and served with his secret, tomato-based Mambo Sauce. They were sold ten for a dollar. We are indebted to Steve Cichon for first reporting the telephone book entry.

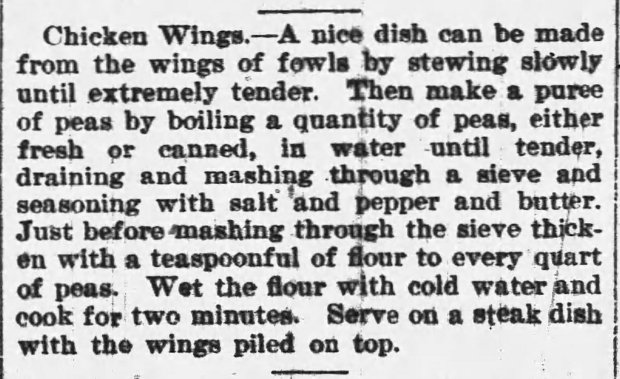

We can look even further back than the 1960s for evidence of chicken wings on the plates of Buffalonians. On August 16, 1894, the Buffalo Commercial Advertiser published this less-than-appetizing recipe for chicken wings:

We have no way of knowing if any 19th century Buffalo households had a copy of The Modern Cook by Charles E. Francatelli (11th edition, 1858), but in it we found this wing recipe, which also sounds fairly unpleasant:

We can, however, show that Buffalo’s chicken wing pedigree began at least 160 years ago. In our menu collection is a Bill of Fare dated July 1, 1857, from the Clarendon Hotel at Main & South Division:

The wine list was longer than the food list. However, in small print, under Entrees, one finds not only the delightful Macaroni baked, with Cheese, but this offering: Chicken Wings, fried. Buffalo comes by its association with chicken wings honestly.

The Clarendon Hotel, shown above in an illustration from Picture Book of Earlier Buffalo, p. 157, was built in 1849 as the Phelps House. Under the new management of Captain Henry Van Allen, it was renamed the Clarendon in 1853 and described as a “first class, well kept” hotel. That year, the Buffalo Daily Republic reported, with a cryptic reference to earlier labor difficulties:

At the Clarendon Hotel, girls have been introduced as waiters, with good success. They get from $6 to $8 per month. No other of our principal Hotels has yet tried them. The proprietors think that the employment of girls will alone exempt the Hotels from a repetition of the annoyance already experienced.

Daily Republic, May 3, 1853

Also in 1853 was this episode of bravery concerning an omnibus, a horse-drawn passenger vehicle:

An omnibus, standing at the Clarendon this morning, while the driver was attending to some baggage, started off, and proceeded down Main Street at full speed. When nearly opposite Swan Street a colored man named Jackson started out and caught the lines and stopped the team, amid the applause of several by-standers.

Daily Republic, Sept. 3, 1853

The Clarendon Hotel served the traveling public and boarders until Nov. 10, 1860, when it was destroyed by fire. At least four guests and two chambermaids lost their lives. Today it is the site of Fireman’s Park, between 1 M&T Plaza and the Ellicott Square building. We hereby credit the Clarendon Hotel as the first known establishment in Buffalo to hire waitresses and to serve chicken wings.

Cynthia Van Ness, MLS

Director of Library and Archives

•This article was featured in the 2017 Summer issue of The Album. To learn more about Buffalo-area food & restaurant items in the Library’s collection, see this list maintained by Library staff.

Starting in the mid-1960s, a Greek immigrant named James Eoannou purchased his friend’s concession pushcart and began selling popcorn, peanuts, and corn-fritters in North Buffalo neighborhoods. He later moved to Delaware Road and began servicing the suburban neighborhoods in the Town of Tonawanda and the Village of Kenmore. One of the signals that summer had come to Buffalo was the arrival of the popcorn man. James was a full-time cook for the Buffalo Athletic Club and loved to go for long, rambling walks. He decided to put his walks to good use and bring some joy to children, and often the adults, of these neighborhoods.

Starting in the mid-1960s, a Greek immigrant named James Eoannou purchased his friend’s concession pushcart and began selling popcorn, peanuts, and corn-fritters in North Buffalo neighborhoods. He later moved to Delaware Road and began servicing the suburban neighborhoods in the Town of Tonawanda and the Village of Kenmore. One of the signals that summer had come to Buffalo was the arrival of the popcorn man. James was a full-time cook for the Buffalo Athletic Club and loved to go for long, rambling walks. He decided to put his walks to good use and bring some joy to children, and often the adults, of these neighborhoods.

2. Read a newspaper published the day you were born. We have Buffalo newspapers on microfilm from 1811 to about 2011, including Polish and German papers published here. We can get out y

2. Read a newspaper published the day you were born. We have Buffalo newspapers on microfilm from 1811 to about 2011, including Polish and German papers published here. We can get out y 5. Look at Buffalo & Erie County atlases. We have roughly one per decade from 1850 to 1950, with a few gaps. What’s great about them is that they show footprints of individual houses & buildings that used to be there or might still be there today. You can look at them one by one and see when your house first appears, which helps you narrow down when it was built.

5. Look at Buffalo & Erie County atlases. We have roughly one per decade from 1850 to 1950, with a few gaps. What’s great about them is that they show footprints of individual houses & buildings that used to be there or might still be there today. You can look at them one by one and see when your house first appears, which helps you narrow down when it was built. In our upcoming World War I exhibit, “For Home and Country”, we will be featuring an oil painting by Lt. Clement C. Beuchat, entitled “78 Lightening Division at Thiaucourt, France, 1918”. This piece depicts a group of World War I soldiers on horseback in the town of Thiaucourt, France, most likely illustrating the remains of the town during or after the Battle of Saint-Mihiel.

In our upcoming World War I exhibit, “For Home and Country”, we will be featuring an oil painting by Lt. Clement C. Beuchat, entitled “78 Lightening Division at Thiaucourt, France, 1918”. This piece depicts a group of World War I soldiers on horseback in the town of Thiaucourt, France, most likely illustrating the remains of the town during or after the Battle of Saint-Mihiel. While doing the research on this painting and Clement, I learned that Beuchat was an original member of the Saturday Sketch Club in Springbrook, New York along with other artists such as Arthur Kowalski, Harry O’Neill, William J. Schwanekamp, and Julius Lankes.

While doing the research on this painting and Clement, I learned that Beuchat was an original member of the Saturday Sketch Club in Springbrook, New York along with other artists such as Arthur Kowalski, Harry O’Neill, William J. Schwanekamp, and Julius Lankes.  This is notable because there is a sketch box used by Buffalo painter and engraver, J.J Lankes as part of the Saturday Sketch Club, in our collection. The Saturday Sketch Club was formed in reaction to the dismissal of Mr. Earnest Fosberry, an artist and teacher at the Buffalo Fine Arts Academy. A group of students, including those mentioned above, created this art school with Mr. Fosberry as their instructor and critic, as a way to protest the firing of their favorite teacher.

This is notable because there is a sketch box used by Buffalo painter and engraver, J.J Lankes as part of the Saturday Sketch Club, in our collection. The Saturday Sketch Club was formed in reaction to the dismissal of Mr. Earnest Fosberry, an artist and teacher at the Buffalo Fine Arts Academy. A group of students, including those mentioned above, created this art school with Mr. Fosberry as their instructor and critic, as a way to protest the firing of their favorite teacher.

The students would meet at a cabin out in Springbrook, NY to immerse themselves in nature. They all had their own sketch boxes with attached seats that were portable and could be carried throughout the surrounding area to set up a painting station wherever they liked. The sketch boxes, like the one in our collection, were made up of wooden boxes attached to wooden folding stools that had multi-colored canvas seats for the artists to sit on while they worked. The boxes opened on metal hinges that locked to create makeshift easels. Inside the box would be all the tools an artist would need including a wooden palette, paints, paintbrushes, and charcoal.

The students would meet at a cabin out in Springbrook, NY to immerse themselves in nature. They all had their own sketch boxes with attached seats that were portable and could be carried throughout the surrounding area to set up a painting station wherever they liked. The sketch boxes, like the one in our collection, were made up of wooden boxes attached to wooden folding stools that had multi-colored canvas seats for the artists to sit on while they worked. The boxes opened on metal hinges that locked to create makeshift easels. Inside the box would be all the tools an artist would need including a wooden palette, paints, paintbrushes, and charcoal.

In 1987, Julia Boyer Reinstein, historian and architectural preservationist, donated over 80 quilts and bed coverings to The Buffalo History Museum. Early on in her life, Julia became fascinated with quilts and believed in the importance of documenting their histories. She received a Bachelor’s degree in History from Elmira College for Women in 1928, writing her senior thesis on early American quilts. Beginning her collection with family quilts, she focused her collecting goals on quilts made west of the Genesee River. Remarkably, only twelve of the quilts in her collection were purchased, the rest were given to her as gifts or through inheritance.

In 1987, Julia Boyer Reinstein, historian and architectural preservationist, donated over 80 quilts and bed coverings to The Buffalo History Museum. Early on in her life, Julia became fascinated with quilts and believed in the importance of documenting their histories. She received a Bachelor’s degree in History from Elmira College for Women in 1928, writing her senior thesis on early American quilts. Beginning her collection with family quilts, she focused her collecting goals on quilts made west of the Genesee River. Remarkably, only twelve of the quilts in her collection were purchased, the rest were given to her as gifts or through inheritance.  Pictured is a red and white Chimney Sweep quilt from Julia Boyer Reinstein’s quilt collection, also known as an Album or Autograph quilt. It was pieced together by Eliza Graves (later Pickett) between 1852 and 1853, and was assembled and completed in 1854, in Perry, NY. Eliza Graves, pictured above, was Julia Boyer Reinstein’s great grandmother. The Chimney Sweep pattern was very popular for Album quilts in the mid-19th century because a name or inscription could be written on the central cross of each block. According to oral histories from the family, the blocks of this quilt were originally autographed, in pencil, by the young men of Castile, NY.

Pictured is a red and white Chimney Sweep quilt from Julia Boyer Reinstein’s quilt collection, also known as an Album or Autograph quilt. It was pieced together by Eliza Graves (later Pickett) between 1852 and 1853, and was assembled and completed in 1854, in Perry, NY. Eliza Graves, pictured above, was Julia Boyer Reinstein’s great grandmother. The Chimney Sweep pattern was very popular for Album quilts in the mid-19th century because a name or inscription could be written on the central cross of each block. According to oral histories from the family, the blocks of this quilt were originally autographed, in pencil, by the young men of Castile, NY.

My personal favorites are the newly developed history kits, proven to be an effective teaching tool that students will love; the Native American Kit and the Pioneer Kit have artifacts, reproductions, mini posters and an activity book and are available to rent for your classroom. These kits have been met with rave reviews. You will also have the opportunity to try your luck at identifying an artifact from the early 1800s as you examine our Artifact Detective Program that can be presented at your school.

My personal favorites are the newly developed history kits, proven to be an effective teaching tool that students will love; the Native American Kit and the Pioneer Kit have artifacts, reproductions, mini posters and an activity book and are available to rent for your classroom. These kits have been met with rave reviews. You will also have the opportunity to try your luck at identifying an artifact from the early 1800s as you examine our Artifact Detective Program that can be presented at your school.